A Lesson on Leonardo from Chuck Smith

Acquired Learning versus Creative Absorption

Everyone called Mr. Smith by his name, Chuck Smith. He was a short, athletic man in his mid-thirties, tan with long blonde hair, which was thinning. His vintage mustache was a perfect match for his early 70's look, even though it was almost 1980. He was my favorite high school history teacher, an energetic storyteller of Western Civilization, and was popular among the student body. He would pace in front of the class, occasionally ducking behind the lectern to check his notes, then a few quick steps to the chalkboard to scribble important dates and names for us to write down. He would use his arms to emphasize his stories, running one hand through his fly-away hair often, and then two hands on his head for a brief pause, as if to say "Wow...mind blown!" about a particular point he just made. Chuck Smith would lecture with such enthusiasm that white spittle would project into the front row of the class. Some would settle in the corners of his mouth after a full hour of animated lecture. I sat in the back row.

Tamalpais High School was built in 1908 in Mill Valley, California with multiple buildings on a campus that rose from the San Francisco Bay into the hills of Marin County with a clock tower as the main feature. The time from the tower was always suspect, if it was working at all. Once the bell rang at 8:20 a.m. for the first class, telling time from the clock tower was unnecessary; I would navigate from class to class with the ringing of the bell and by following streams of students on ant trails to our next class. A couple of portables where installed above Keyser Hall and Wood Hall to make room for a growing class size. It was an unusually warm spring day so Chuck Smith kept the door of the portable classroom propped open. Sunlight streamed across the front of the classroom and would backlight his hair like a halo in a Renaissance painting.

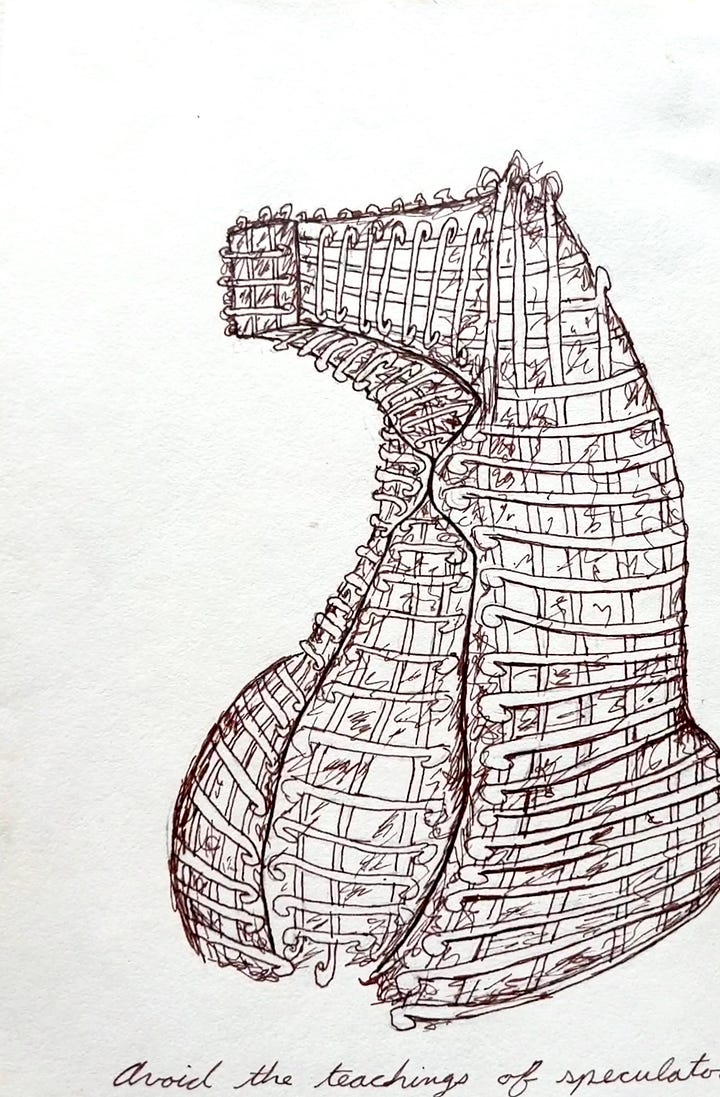

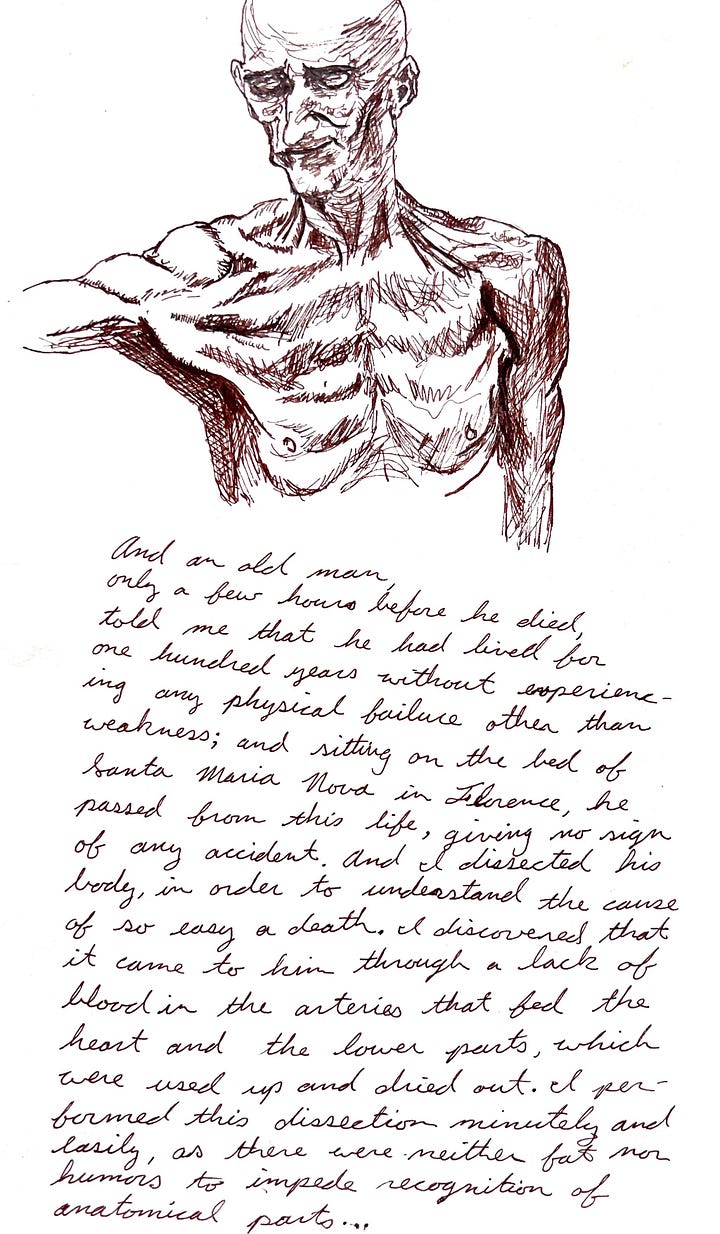

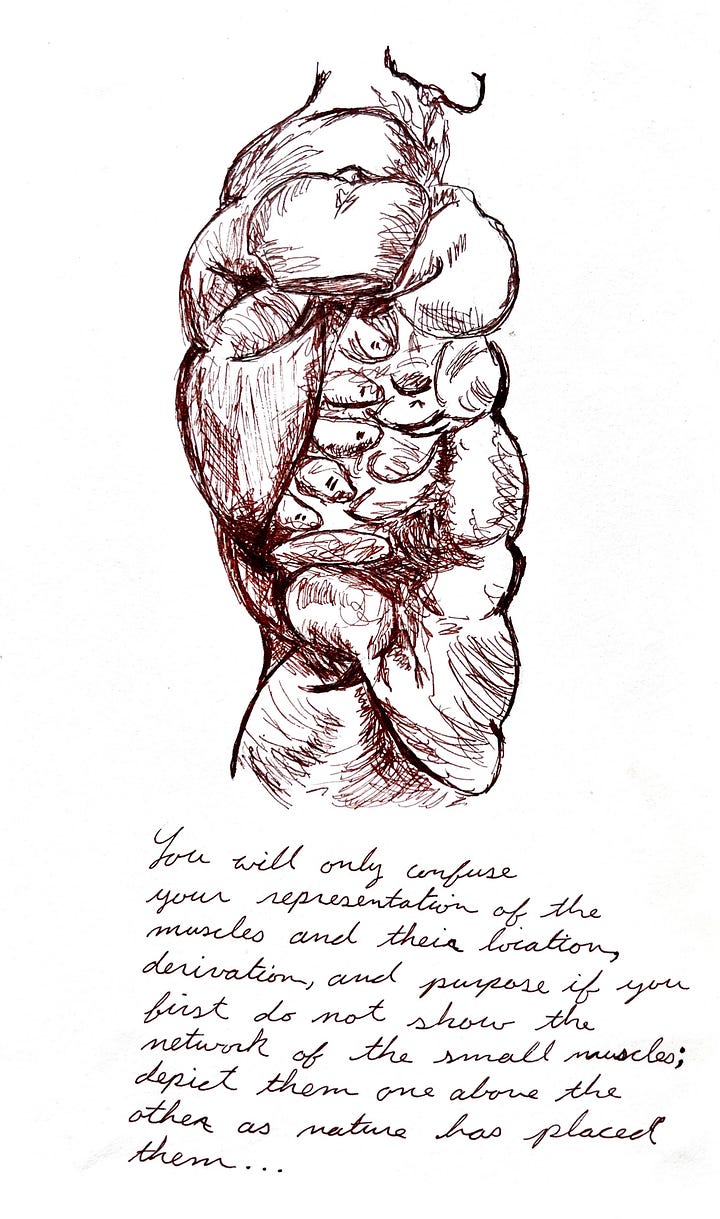

I stayed after class to ask Chuck Smith a question about the end-of-semester report that would make up half our grade. He had just finished an inspiring lecture on Leonardo Da Vinci. My interest was piqued but I was reluctant to write another boring research paper. I tired of the ordinary and the thought of starting a project at the card catalog in the library, choosing at least three books for reference, scribbling notes on index cards, and carefully adding footnotes to identify my sources was a boring approach to me, not worthy of the Renaissance master. He left behind journals full of sketches and notes on anatomy, flying machines and machines of war, and how shadow and light on the human body, or the muscles of a horse, or the folds of draped fabric could be rendered realistically with a charcoal pencil on paper. Chuck Smith suggested he would accept something creative based on his journals, as long as I was one hundred percent invested.

Although our high school library was adequate for basic research, I had at my disposal a public library built into nature with a creek flowing through a grove of redwood trees just a short walk from downtown Mill Valley on Throckmorton Avenue. It was built in 1966 with floor-to-ceiling windows, a wood-burning fireplace and hand-crafted furniture made from walnut. It wasn't just a building with books, it was an ecosystem of architecture and nature, a place for contemplation where I could take a break on the deck overlooking the redwoods, hear the rippling of Old Mill Creek below and listen for birdsong. It was the perfect place to read through Leonardo's journals and decide on the direction of my project.

On my way home I stopped by the art store on Miller Avenue. I liked to wander through the aisles and imagine how I could create something from all the pens, paints, paper and canvases, but never did. For some reason I now believed I could recreate many of the sketches from Leonardo's journal, assemble them in a portfolio, add simple captions to describe the drawing as my semester-ending project. What I didn't know was if I could even draw that well and how much time it would actually take. I sampled a sketch pen with a narrow tip with brown ink on a tester pad. I wrote Leonardo's name, I turned the tip at an angle, I made circles and chicken scratch. What I liked most about the pen was the color. The rich, brown ink turned to a sepia color on off-white art paper and looked like the aged drawings in his journal. When I got home I went straight to work.

I started with a pencil and eraser, looking at his self-portrait as an older man, then drawing what I saw: his eyes and bushy eyebrows, long hair and beard. When I was satisfied I begin with the brown art pen, following my pencil strokes, adding more here and there, until hours later, I was looking at a duplicate of his sketch. I was lost in time, each pen stroke a connection to the master himself, a journey across five-hundred years. I continued with additional drawings that intrigued me — a one-hundred year old man, the torso of a young man that revealed muscle structure and placement, the same of a horses head and hind quarters, a Trojan horse, and weapons of war that he designed. It took two weeks and many hours of drawing quietly in conversation with Leonardo, creatively absorbed in his life and work. I can't imagine having the same experience writing a term paper.

I handed in the project and forgot about it. After Spring break Chuck Smith asked to talk to me after class. He asked if I had seen the glass display case in Wood Hall, just next to the principle's office, and if not I should go now. With anticipation, I walked there first knowing it would make me late for my next class across campus. Behind the glass at eye level was my project with the pages displayed and a note with my name. Chuck Smith found a way to engage me in learning by acquiring knowledge through creative absorption in a way that has continued to this day. I have lived a creative life.

Chuck Smith died in January 1990 from HIV/Aids. For years after graduation I would occasionally drive past the high school around lunchtime and I would often see him jogging the perimeter of the athletic fields. He still had his long blonde hair, still thinning but flowing, aided by the breeze coming off the Bay. There was never any talk about his sexuality. There was never a need. Growing up miles from San Francisco I had an early education in humanity, a humanity that Chuck Smith upheld in his teaching and the connections that he made with his students.

Another fine piece of writing about a slice of your life. Thanks for the enjoyable reads.