A Place of Belonging

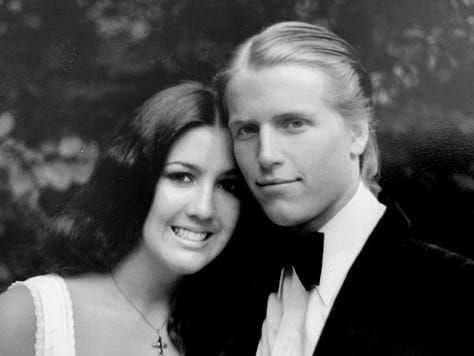

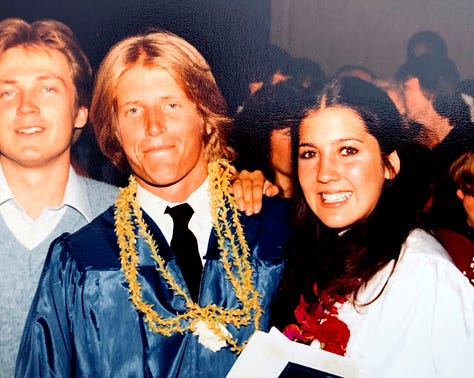

Our kitchen table—memories on our 45th wedding anniversary

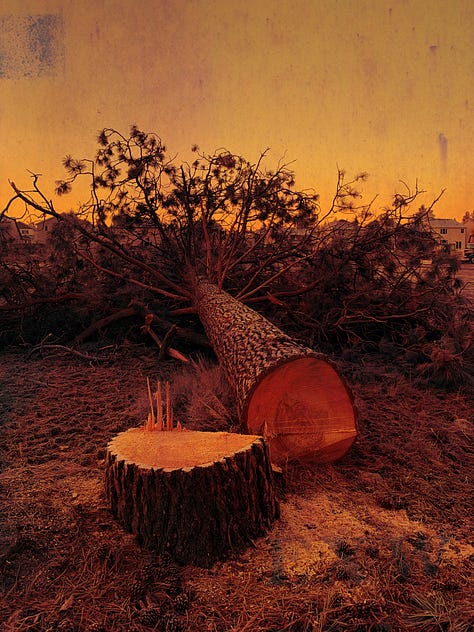

The woodsman took a mighty swing with his axe at the trunk of the pine tree in the English forest near the mill and the village where he lived. He needed to create a groove through the thick bark near the base of the tree revealing the white wood underneath to have a nice start for the cross cut saw. It would take two men over an hour, back and forth, occasionally removing pulp that would bulk in the teeth of the saw. It was the largest pine tree in the area of potential trees to cut and deliver to the miller for sawing into planks.

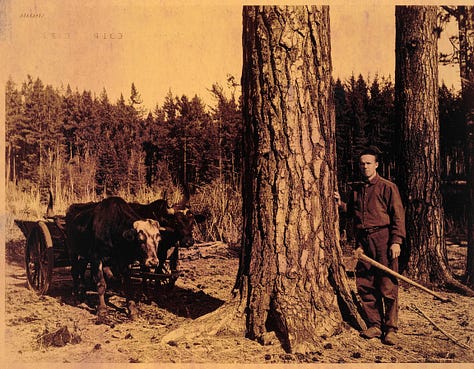

The tree hit the ground with such impact that the earth shook under the woodsman’s feet and unsettled the two oxen waiting to haul the tree out of the forest. The chains that were hanging from the oxcart jangled and the large wheels rocked back and forth as the oxen shifted their weight, then settled again. The interior of the tree revealed its tree rings, one layer of various thickness representing each year its been alive. The woodsmen weren’t interested in the age of the tree, just its size and straightness and value. The birds, noisy and disturbed at the beginning of the cutting and sawing fell quiet, a funerary silence for the tree that was once their home.

Just as there is an art to felling a tree, hauling the tree has it’s own art form, wrapping the chains around the trunk, interweaving between the strongest branches, then using the muscle of the beasts to achieve what seems like an impossible endeavor, moving the tree to the mill, a mile through the field at the edge of the forest. With many false starts, using the lash of the whip and slapping of the reins on the oxen’s backs, the men barked out orders to move. Once they got initial movement, first a few inches then a foot and finally enough momentum to achieve a gradual speed forward, the bulls slowly charging ahead digging their hoofs into the black soil, their necks straining in the yoke.

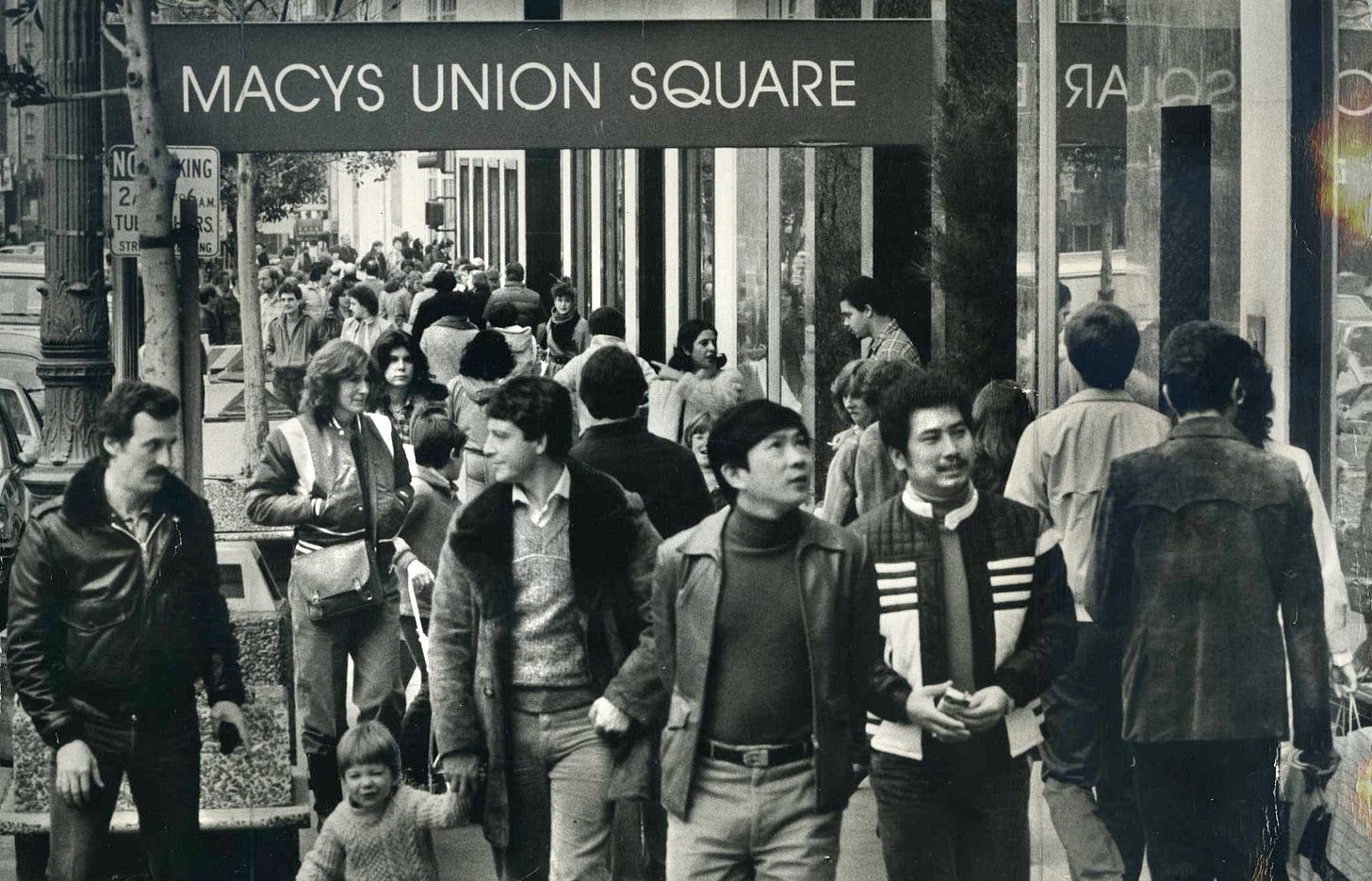

My father-in-law, Bill Withers, was a Senior Vice President of Visual Merchandizing for Macy’s California. He was based in San Francisco after working for years in Los Angeles for the May Company as a window dresser, then in New York City for the original Abercrombie & Fitch in the 60’s, then a sporting goods store established in 1892 selling high quality camping, hunting and fishing gear. He was the designer in charge of all displays, including the windows when window shopping was in vogue in large cities, and strolling on the sidewalk looking in allowed many to dream of the possible. The windows during Christmas were especially magical. Bill was an artist through and through and found a path in a career that supported his family.

Once in San Francisco working for Macy’s, Bill was in charge of the Annual Easter Show that became the biggest display of flowers in the history of The City. Positioned next to Union Square in the heart of the retail district and in a time long before screen culture, each window was a virtual screen in itself, using merchandise for sale in the store to tell a fashion story, mannequins framed in the window box, a canvas of color and design. For the Easter Show each window was an explosion of flowers of every variety—white lillies from Japan, poppies from Holland, and roses from England displayed on a simple pine table floating against a white background. Designers like Ralph Lauren, Tommy Hilfilger, and Yves St. Lauren would vie for coveted space in a window near the front door opposite Union Square. One year he fabricated a life-size pegasus with animatronic wings festooned with flowers that hung 20 feet in the air that greeted customers at the main entrance.

Once the display furniture that Bill purchased in New York served its purpose in the store it was inventoried to the basement. Bill would eventually acquire his favorite pieces at a discount. This is when we were gifted our 150 year old English pine table we’ve used for every meal and the centerpiece for our family for the last 45 years.

It came to us well used with 150 years of markings and a peculiar triangle-shaped depression in one corner. It looked like a shape from an iron so a story was born that the table was used on a ship as a ironing board and the iron, heated from a wood stove, would smooth the thick cotton sheets before being set down at the corner making a depression in the table over time. Maybe it was on a ship that crossed the Atlantic with first class cabins where a change of sheets was expected? Maybe it traversed Cape Horn and was used in the captains quarters to roll out maps and chart direction? Maybe it was just a tenant farmer’s table in the Cotswalds, used for decades for hearty breakfasts after milking the cows, for ironing in the afternoon, and dinner after plowing the fields? Our kids did their homework on it, I went back to college and wrote essays on it, Annie decorated the table every birthday and holiday, and played cards with her friend, Antoinette. Every activity left its mark as the wood absorbed spills and cuts and scratches. More than anything, the table collected stories of living preserved with a coat of wax every few months. If there was an AI machine to download a transcription from it’s old wood it would fill a shelf in the history section of a library.

Now close to 200 years old, the table has meant everything to me and my family. It’s imperfections it’s acquired along the way, it’s tongue and groove construction has held up without any repair. It makes some creaks and groans when we move it. It seats six with room on the corners for grandkids on stools, can be extended for big crowds with a plastic fold-up table butted edge-to-edge and covered with a Norwegian table cloth. We hosted twenty-two people one Thanksgiving, adding extra fold-up tables and chairs borrowed from the bakery where Annie worked. The pine table was always the solid foundation of our holiday meal.

More than anything, the simple family dinners served in our home on our kitchen table is the bond that continues, tying the everyday to the seasons, to the years, to the decades. When our daughter came home from musical theater rehearsal in high school and the boys came in from football practice, uniforms muddy and wet from the Portland fall rain, it was ritual. Windows in the kitchen would steam up from the boiling pasta water, the bolognese sauce ready to serve after simmering all afternoon, a new canister of parmesan cheese ready to pour, and a heaping plate of garlic bread broiled at the last minute and placed in the center of the table, almost too hot to touch. Annie would always light a candle that would focus the meal, the golden flicker of the flame reflecting on the warm patina of the pine table, the faces of our children a Rembrandt painting, the table’s complex molecules awakened from it’s days in the forest, knowing it’s purpose in our kitchen.

When I was diagnosed with metastatic cancer to my brain, I faced the end of my life with my elbows on the table, my face in my hands, a bowl of oatmeal in front of me but unable eat, Annie by my side. With each remission, a celebration of clean scans with a marzipan Princess cake, adding another tree ring to the core of my being. When the cancer recurred, I sat at the table and wrote stories.

I wonder what our table’s next incarnation will be and what stories it will collect. Will someone 100 years hence tell a story of us? A great-great-granchild, perhaps? Sometimes I think I hear birds singing from the long-ago tree in an English forest. Or could it be the birds outside our window singing with the sunrise? Maybe both, singing together, an echo across time, a pine tree that fell to earth to be resurrected in a new form—our table, the center piece of our life. A place of ritual. A place of belonging.

I love this Lars! And I felt it, reconnecting with you and Annie over that table in Hood River! And I enjoyed hearing about Annie’s father! Did you know the M and F visual department was just down from the studio you worked at with me? I hope to sit with you at that table again soon!

I love this! Your story, as always paints a picture so clear that as the reader we are standing right beside you. 💕 The table, the memories, the love and lasting friendships all because you and Annie are so special. It’s time for a family book! 😉