A Remembrance

I was digging through a box of old photos and two old polaroids rose to the surface, like panning for gold and gold flakes appear on top of the water. The polaroids were of me when I was nineteen years old and I spent 2 months working in Japan. I was being paid to stand in front of a camera, a six foot, blonde, blue-eyed representation of all things Western, a fixation of a new generation in 1982 Japan on American culture after a complete rebuild of their cities and way of life after WWII. Jogging through a large park in Tokyo I would come across countless groups of teenagers dressed as Elvis Presley, girls in Poodle skirts, dancing around a large boom box blasting a cassette tape from American Graffiti. I was introduced to a culture that would influence my life, that now, at sixty-two, I only am beginning to understand.

I visited a Buddhist temple in Kyoto and felt an ancient sense of peace, of raking sand in the middle of a rock garden into a perfect design, or trimming bonsai trees into a controlled representation of the wild forests of nearby Mount Fuji, a religion without religion, a philosophy that appealed to me. I felt the clarity of opposites—of joy and pain, beauty and ugliness, serenity and chaos, the Tao of black and white, the Yin and Yang—that revealed many questions I had as a young man. The daily task of the monks were tangible chores that seemed a way forward. I wanted to rake my rock garden and tame the wild forest of my inner life like the monks. In my naïveté of youth—and desperately hoping for a shortcut to enlightenment— I didn’t know it would take a lifetime of searching only to find that I was raking all along, tending my garden, chopping wood and carrying water, eventually maturing beyond the anxiety of youth, finding an acceptance in the polarity of life, the sun, the clouds and the sun again.

One Japanese word I learned held a truth that I’ve come to know: Kintsugi.

“…the Japanese art of Kintsugi, in which a broken thing, such as a shattered piece of pottery, is reassembled with gold or silver lacquer to create something new and wondrous,” an appreciation of the beauty in the imperfection and impermanence in life (from a NY Times article).

The fullness of this philosophy, born of thousands of years of survival in the islands that make up modern day Japan, is a reminder to accept the cracks in life we all face, to find hope in imperfection and the soulful function of impermanence—families serving rice at dinner, a long crack running up the side of the bowl, repaired yet still useful, serving as a prayer that any brokenness in the family can be healed. Or a rice farmer in the country, bent over all day harvesting his meal, accepting what feels broken in his body, then awakened at dinner to his repaired rice bowl before him. The wounds we heal in ourselves, and always with the help of others, we make ourselves useful in the world.

Tokyo

I stepped off the plane at Narita Airport outside of Tokyo and navigated through customs and found my bag on the luggage carousel. The agency that had sent for me told me what to do next: find the ground transportation to the downtown bus terminal where I would be met by Max, an employee of the agency. I had awakened at three in the morning the day before and said goodby to Annie and our daughter, Katrin, sixteen months old. We both agreed this trip had to be done if we hoped to get our own apartment and move out of Annie’s parent’s house after getting married three months after high school graduation. The sadness of my departure was mixed with the excitement of adventure, a “heroes journey”, as Joseph Campbell said, to go out into the world and conquer dragons and return home a better man, a better husband, a better father.

At the Tokyo bus terminus, I waited for my bag. As I looked around for anyone that might be Max. I stood a head taller than most so my gaze was lost in a sea of black hair of people crowding the conveyor belt. My bag was one of the last out. Just as I was starting to worry that I would be orphaned in Tokyo, a young man approached, a little breathless. “I’m here to pick you up’” he said and introduced himself as Max. He tried hard to say my name, “L” being a hard letter for native Japanese speakers. This I got used to over the 2 months in Japan, a noble attempt by clients to pronounce my Norwegian name, Lars, with a tongue never challenged to perform the oral gymnastics. Most people managed a “Wah-s” with an added “san” at the end, a gender-neutral sign of respect akin to Mr/Mrs/Ms. Wah-s San was my new name.

Max carried my bag to a taxi and we were off through the heart of Tokyo at midnight. We passed the old Emperor’s complex, the sky scrappers in the financial district, the Ginza shopping district lit up by neon, then through neighborhood streets until we reached the studio apartment I would share with another person for the next two months. But for a brief moment of excitement in the taxi feeling like I was in a James Bond film, the tiny apartment dropped me into reality. There was a single bed on one wall and a fold down couch on the other, which Max pointed out was mine. A set of thin sheets and a tiny pillow—everything was tiny—was laid on the couch and my first night was ahead of me with my feet hanging over the arm of the couch. Max left me a hand-drawn map to get to the agency in the morning, a ten minute walk, he assured me. Before he left I asked him what his Japanese name was. “Makato,” he said. I only called him Makato after that.

I awoke into the unknown and into a life I didn’t plan, away from my wife and daughter, away from everything I knew. Beyond the map Max left me, my life had no direction, a blank canvas to be painted by others, a collage of exotic, black brush strokes in Kanji and large, colorful Yen banknotes. I met the agency owner, Miyako, and her assistant, Junko, and of course, Mikato was there, seeming proud of his junior assistant status and his ability to deliver me to this moment. They shared good news that they had circulated my portfolio before I got to Tokyo and I had confirmed bookings for the next month and felt confident they would book the second month as well. Miyako and her staff all smiled at me, a commodity that would bring them commissions, a money maker, an agency work-horse, an investment in airfare and apartment fees, which, I later learned, would be paid back out of my earnings. Some models come with high hopes but don’t work at all. A bust for the agency and the model. My mission was to make money, to convert yen to dollars to send home, and return in 2 months with enough money to start our new life. I was starving so I asked them about food and they directed me to a noodle bar a half block from the agency.

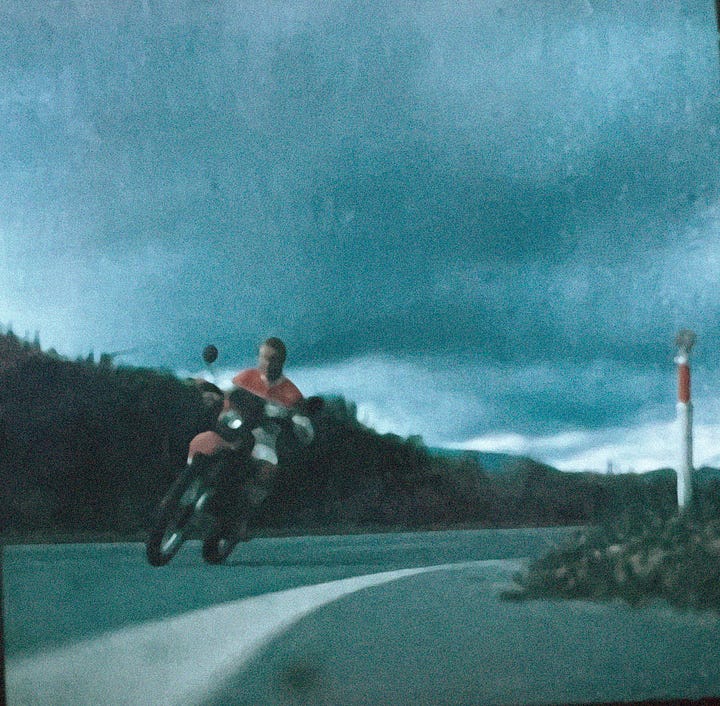

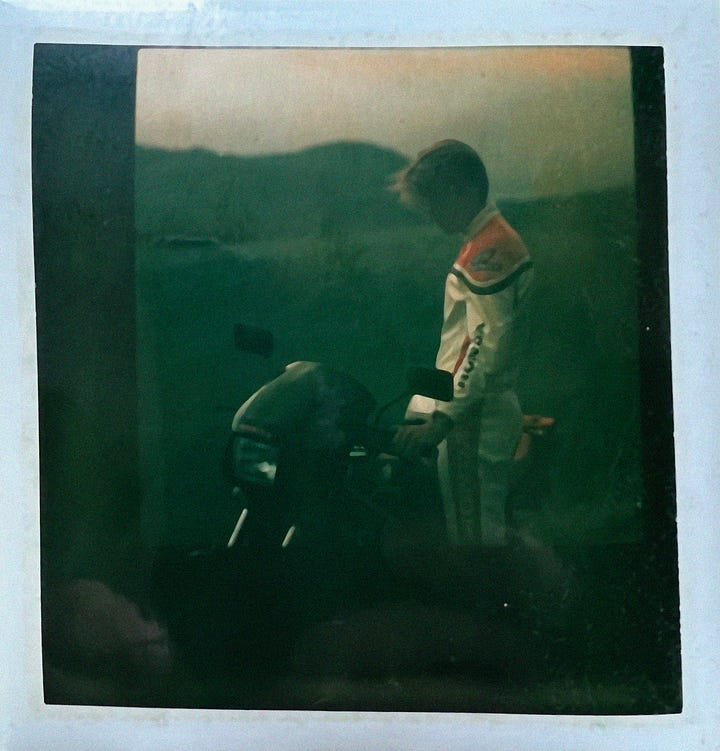

That afternoon, back at the agency, I learned I booked a job for Honda Motorcycles, a one week trip to shoot the 1983 catalogue on the Northern island of Hokkaido. I was to fly there the next day. That was the last day I had off in the 60 days I spent in Japan.

Hokkaido

I knew of Sapporo from the 1972 Winter Olympics and the bottled beer my father-in-law would order at Ichiban in San Francisco, and later at Samarai, in Mill Valley. I wasn’t of legal drinking age so he had to order it for me. That wasn’t a problem in Japan. They treated me as if I was royalty. I was often referred to as David Bowie, as if anyone with my coloring might resemble the pop star. The client and crew on the Honda job treated themselves with a large budget, just as happy to get out of Tokyo and into the nature and traditional culture of Hokaido as I was. Honda shipped their new line of motorcycles to the island from the factory, ready for their close up. After a night in Sapporo, we left for the north country for scenic backdrops to photograph different scenes of models and the motorcycles, usually traveling during the day and shooting with the golden hour in the early summer evening. We stayed in traditional inns called Ryokans, complete with tatami mats, futon pads, communal baths, a yukata—a cotton, kimino-like robe—to wear to the bath house, and a multi-course dinner at a long, low table, all sitting cross-legged on the floor, still in robes, with course after course of mysterious creatures from the sea served by woman dressed in full geisha costume. There was plenty of Sapporo beer and whiskey drunk. After a coma-induced sleep and a bowl of miso soup for breakfast, we set off for the first location on the other side of the mountains.

On the last night of the week-long shoot, we stayed at a private residence in Sapporo, like today’s AirBnB, or a German Guesthaus, with communal rooms of futons laid out on tatami mats with sliding rice paper doors for privacy. In keeping with the clients joy in spending their clients money we went to a special celebration dinner where they grilled fish on an open flame in front of us as the whiskey flowed. I had one to clink “Kompai!” but decided not to join the crew on a late night adventure to a bath house. A taxi dropped me off at the nearest intersection to our lodging but it took me an hour looking for the right door in a row of identical houses, opening unlocked doors at two in the morning, entering, then deciding I was in the wrong place. One looked familiar so I continued upstairs and found my futon, thankful that gun ownership in the home doesn’t exit in Japan.

Kintsugi Lived

I returned home to San Francisco two months later a hero, as Campbell predicted, pockets filled with cash, dragons slain, my soul wiser, my heart stronger. I met Annie and Katrin in Hawaii for a week in Maui. Waiting at the gate for them to arrive in Honolulu was one of the most extreme emotions I’ve ever felt in my life. My knees buckled as we embraced in a puddle of joyful tears. Landing in Maui, the confidence I gained while away was dashed when we were turned away from the rental car counter because I was under age. Once settled, It only took one day to experience Kintsugi when Katrin was jumping on the bed of the hotel room, flew off and hit her forehead on the edge of the side table, opening a gash that took five stitches to close. Going from a tearful hug at the airport to holding down our screaming 18 month old to get stitched up by the shaky hands of an old pediatrician in Lahaina, I learned my own evolution is superseded by the needs of others, my enlightenment found through raising children. I was responsible for keeping our little family’s garden raked, fixing cracks as they occurred—which was often. Katrin’s stitched-wound was a crack large enough to feel deeply with only time and the gentle waves of the white-sand beach to heal. I paid the doctor in cash and went to Sunday brunch.

At 42, with three children, I started a new hero’s journey: cancer, a fight with dragons using chemicals, radiation, and surgery to rid me of the rogue cells. We all raked together as a family. At 62, with eight grandchildren, and multiple cracks visited upon me as a recurrence of cancer, I see in my body and my family a spirit of golden hope that helped heal me. I became usable again, a rice bowl to serve, my stem-to-stern surgical scar a physical expression of the philosophy of Kintsugi, my internal wounds salved by love.

Through surfacing a polaroid of me as a young man riding a motorcycle through an ancient land, I see how far I’ve traveled. I’ve learned to embrace this imperfect and impermanent world to be a vessel of service and sustenance. When I’m no longer able to be repaired I will surrender to the wondrous and beautiful life I’ve had.

Wow! So cool, very much a hero’s journey at nineteen. A different world before the internet in your hand. I love the ceramic bowl with the gold binding the cracks, better than the original. Great intro to Buddhism and the Japanese way of life, but I wanted to learn more the bath house culture.

Another great chapter in a life well lived. Stitch them together in a book. I am so happy you are here.

Thank you for the beautiful story - a funny, I walked past Annie’s family home yesterday and ran into Roddy today. You are in my heart. ♥️ to you & Annie!