Lost in the Sheets

I had a dream of my mom hanging sheets on the clothing line in our backyard on an early summer morning. She had a way of looking at me with a smile, not saying a word, acknowledging the whole of me, a maternal silence that was conveyed loudly by her heart. When I was in the 1st grade I would walk with my older brothers to school but would walk home alone since my grade let out earlier than theirs. No one was home when I got there and I remember that the sheets were dry and moving gently in the breeze. My dream was in slow motion, a cinematic scene borrowed from countless movies we’ve all seen, a close up of a child’s hand, partially outstretched, gently touching the sheets while moving forward. It was unclear to me what was actual memory and what I borrowed to complete the visual in my dream. What was clear was my mom was there, she acknowledged me, and then she was gone.

The sheets hung from three lines stretched taut from two metal posts set twenty feet apart, attached to a horizontal bar on the top of each post. The lines were spaced evenly apart, allowing the sheets room to breath and to use the heat of the sun as it moved overhead during the day, east to west. I had room to maneuver between the sheets while the summer breeze temporarily created a doorway for me to enter, then closing behind me leaving me in a circle of white light. I disappeared from the world, feeling comfortable surrounded in the light filtered through the sweet-smelling cotton sheets, yet anxious at the same time, as if playing hide-and-seek with the possibility that no one would ever find me.

We lived in a Forsthaus (forest house) that was abandoned by the German government after WWII when the U.S. Army built a hospital at the edge of the Northern Palatinate Forest, 90 miles southwest of Frankfurt. The farmhouse and surrounding acres was used by the German Forest Service and housed generations of Forst Meisters and their families that managed the vast resources of the forest. The army hospital, and the farmhouse on the back border of the base, was up a steep hill from the quaint village of Landstuhl, replete with red-tiled roofs and stucco buildings and a cobblestone square with a center fountain and large ceramic pots with red geraniums. The partially reconstructed ruins of a twelfth century castle stood on the opposite hill from the Army base and looked down on the village, a witness to 1,000 years of stories, of people born and dying, farmers bringing food to market, bakers filling bellies with bread, craftsmen making furniture, shoes and clothing. In the case of attacks, the villagers could find safety inside the castle walls while archers repelled invaders from the parapet. For me, it was a playground for my active imagination, running through the castle grounds unbounded after minding my behavior on a tour of the interior.

The Forsthaus stood for decades before the war, a brick and stucco fortress with attached barn and wine cellar, and a large field beyond the yard and the clothing line where my mom grew potatoes. Before the house existed there were settlements of neolithic people, Germanic tribes during the bronze age, centuries of Romans, Charlemagne, the Hapsburg monarchy, the Reformation, various Emperors and Prince’s of early German states before it was unified, Napoleon’s France, and the Nazi regime. In fact, there was a Hitlerjugend Schule (Hitler Youth School) on the site where the hospital now sits. The forest around our house was filled with these ghosts of the past. The footpath I walked for 1 kilometer to school was part of the northern route of the medieval pilgrimage of the Way of St. James (Santiago de Compostela in Spain). Me and my siblings would spend our days exploring these deep woods, wading through creeks catching frogs, building forts and playing war. Standing within the shifting sheets in the ancient air, I could be anything—a knight in shining armor or an archer on the battlement—or I could be a tiny speck of it all, a single strand of cotton woven among millions of fibers, a sheet that might fold in on itself and fall into a black hole.

There was a guard gate at the border of the base and the forest where our driveway met the main road. A solitary booth was manned by a soldier checking the identification of the few people that passed through this back gate. On cold mornings my mom would send us up with a hot cup of coffee to the soldier in the guard post, probably no more than nineteen years old, maybe from Arkansas or Minnesota or New Jersey. We got to know the soldiers that guarded the border. They were a long way from home and lonely and it felt to me, with all my freedom to roam, that the booth was a prison.

Once, my brothers and I stopped by the guard gate to show the soldier our prize bull frog after hunting for frogs for hours in the woods. We would wade through the pools of water that formed every few yards as the small creek wound it’s way through the trees and brush, building volume and current through the joining tributaries and a gradual slope, finally reaching the rocks and boulders that opened into the earth, the creek becoming a small river, the water rushing into a cave my brothers told me was where Bloody Mary lived. When we showed our soldier friend the frog I reverently held in my hands he told us that back home he and his friends would put a firecracker in the mouth of the frogs they caught and watch them blow up. We carried our amphibian friend back to the creek from whence he came and watched him hop away then swim in the shallow pool until he was safely under the embankment.

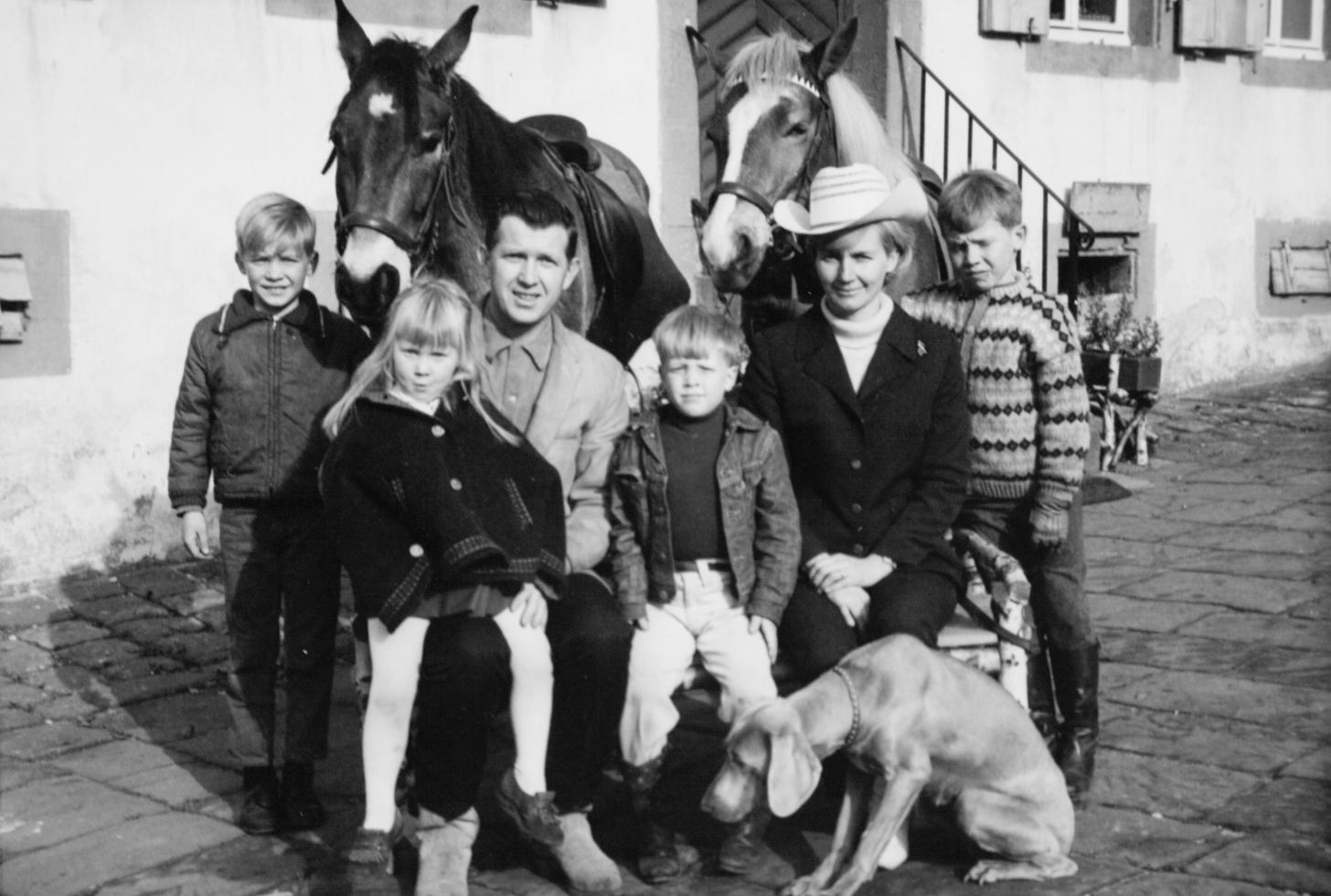

My father was stationed from 1967-1970 at the Medical Center in Landstuhl where I attended kindergarten through second grade at the Department of Defense Dependent School. My teachers were either spouses of military staff or adventurous single female teachers spending a few years working abroad. Most of my classmates lived in the apartment buildings built by the army after the war, every unit the same in layout and design. We lived there too for three months until my parents inquired about the Forsthaus at the local government land office to see if they could rent it. My mom spoke German, which helped, a remainder of the lessons she was forced to take in school as a girl in Norway under Nazi occupation.

My mom made sure that all of her children, my two older brothers and my younger sister, knew that we had a choice in life, that “the path less taken”may lead to a unique and meaningful life, like her emigrating to America for college and marrying my father leaving her childhood trauma of the war behind, or my parent’s decision to bring life, and their young family, to the Forsthaus on the edge of a magical land. Waking from my dream, lost in the sheets, Annie reminded me it was my mom’s birthday. She died when she was 40 years old. She would have been 89. The way she encouraged me to express my true creative nature—a boy at play, scruffy hair with dirt on his cheeks, earth on his clothes, cuts and bruises on his elbows and knees, never bored, and most importantly always loved—contributed to the way I’ve lived my life. At sixty-one that boy is never far away. Waking from my dream and writing down notes to make sense of it, I realized I was not lost in the sheets, I was found.

Wow! You brought me back! What a great recollection of childhood memories woven into the cloth of human history and the hanging sheets. Your writing style brings forth so much emotion, it really is lovely. Time for a book soon!!

A wonderful story that evokes beautiful memories of life in that Forsthaus! What a glorious childhood it was. And I do remember the labyrinth of sheets on that clothes line.....Thanks for painting such a beautiful picture that brings all of those cherished memories buried deep within my brain to the forefront of my mind.