As your 9th birthday approaches I wanted you to know more about the chest I passed on to you when we lived in Bend, Oregon, 2 blocks from each other and before you moved to Valencia, California and Edie and I moved to Hood River, Oregon. As we were packing, I removed a lifetime of letters, postcards, citations, photographs, childhood trophies and momentos from the chest to make room for you to begin to save things that are important to you. But it’s more than a storage container: it’s a Hope Chest that comes with a story about your family.

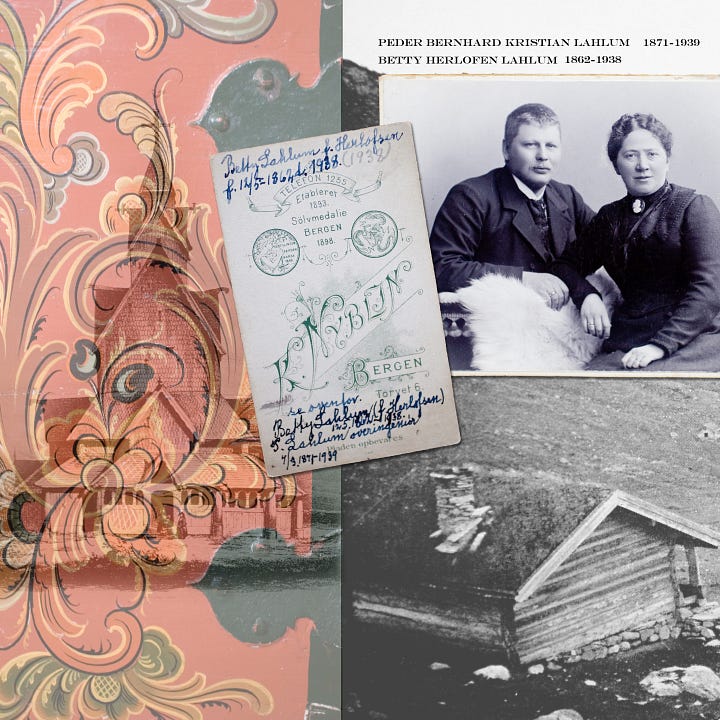

I was named after my Norwegian great grandfather, Lars Moe, who came to America with his mother and 2 brothers from Suldal, Norway in 1872. That’s why Moe is my middle name and it’s painted on the front of the chest. Your mom and dad named you after me. I pass this trunk on to you for a place to hold anything that is important in your life, as I have done. But it’s not the things that are important, it’s the memories that they hold, and how you choose to remember them, the chapters that form the stories of your life.

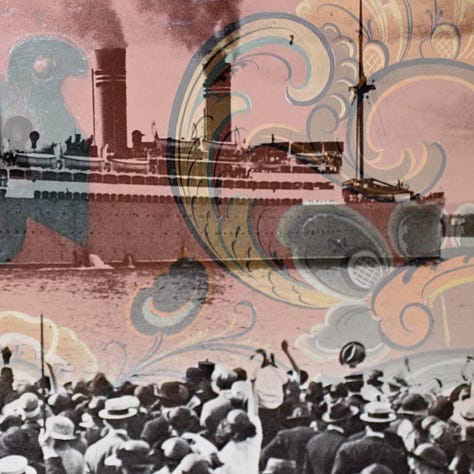

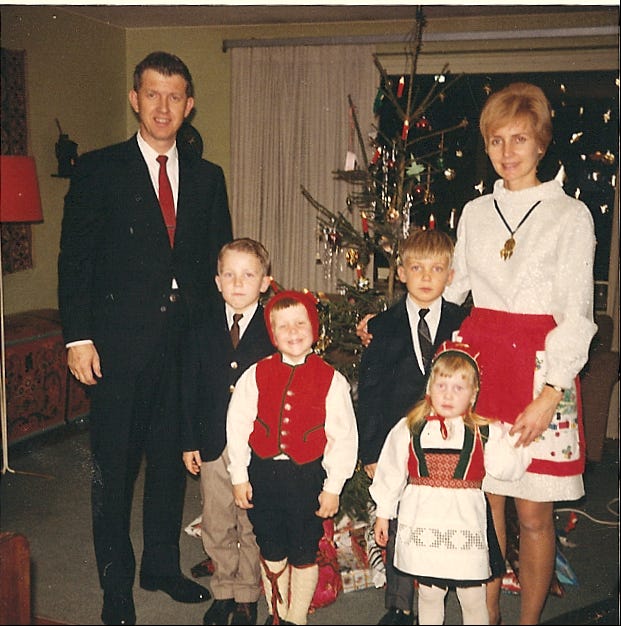

My mom and dad gave me this Norwegian trunk when I was 5 years old. In fact, they had 4 of them custom painted, each chest in different colors; your great uncles Erik (blue) and Richard (red) and you great aunt Britt (yellow) with our names and date of birth on the front. Mine, now yours, is green, my favorite color at the time. They wanted us to always remember our Norwegian family history. This trunk is painted in a traditional Rosemal 1folk art design that dates far back in Norwegian history. It also represents the container that held family treasures that made the long journey across the Atlantic ocean when your ancestors emigrated to the United States from Norway.

I kept many things in the chest over the years: baby teeth the tooth fairy left behind, drawings I made, badges I collected, report cards from school, and post cards from my travels as a kid. When I was 7 years old we lived in Germany and went to Berlin and visited a museum that hosted an Egyptian display of artifacts, including the bust of Nefertiti, a famous Egyptian queen that lived over 3,400 years ago. I was mesmerized by her face, her one glass eye (her other eye was missing when they discovered her) and her oddly shaped blue hat. My mom gave me a Deutch mark (equal to a US dollar) and I bought a postcard of her in the gift shop and kept it in my trunk my whole life. This begun a lifelong interest for me in the history of our world and the many people and civilizations the have come before us.

When I was nine years old I went on a trip to New Mexico with Uncle Knut, Tante Unn and my cousin Kolbjorn from Norway who were spending a year in the States as an exchange teacher in Evergreen, Colorado. Uncle Knut pulled into a long dirt drive off the backroad we were traveling to a ranch house on the horizon, cattle grazing on each as far as the eye could see. Knut knocked on the door to ask permission to pitch a tent on their property for the night. The rancher pointed out a spot by an old windmill and said breakfast was at 6:00.

After we attempted to erect the 6-person tent in the wind, dust circling around us in a mini-cyclone, the rancher pulled up in a pickup truck with a camper shell to offer us a safer and more comfortable night sleep. That evening Kolbjorn and I drove in the open bed of the ranchers truck with bags of feed—big alfalfa pellets as large as polished green river stones I could hold in the palm of my hand. We drove at a slow speed and shook the bags off the back of the truck into the pasture as the mooing mass of cows followed behind us as long as the feed lasted. The teenage son of the rancher showed me how you could eat the alfalfa pellets by biting off half of one in a big snap. I tried it and a green sludge off lawn clippings oozed from my mouth, a cow’s version of a shot of green juice. Or an adolescent joke at my expense. I kept two in my jacket pocket and put it in my trunk when I got home, less of a reminder of the taste of the alfalfa but of sitting around the breakfast table with the rancher, his wife and their six children eating steak and eggs while the sun rose and edged a golden light through the window across the Rockwell setting.

In the 4th grade I got an A on a book report on General George Armstrong Custer and The Battle of the Little Bighorn,also known as Custer’s Last Stand, that I put that in my chest, too. I listened to a record of the same name with a heroic Custer, golden locks waving in the sun, calvary-blue jacket with gold epaulettes, a pistol in one hand and a sword in the other, the last man standing on the hilltop with his charges laying dead or wounded around him. The record used sound effects of gunshots, horses wildly neighing, fallen soldiers crying, and Indians hooping and hollering like all Western’s at the time. Of course, today we know it as pure fiction, a white-washing of history to glorify westward expansion and minimize the annihilation of indigenous people. Custer was likely one of the first to fall.

Many years later I visited the area in South Dakota where the battle took place where the Cheyenne and Lakota Indians, led by Crazy Horse, took revenge on years of broken treaties by the United States. Your dad and Uncle Erland and I went together to visit the battlefield while on a trip back home to Oregon after spending a week in North Dakota visiting your grandfather’s birthplace. As the sun lowered in the sky, the long shadows of the grave markers, painted white and placed where they guessed cavalrymen and Custer fell in defeat, pierced the veil of truth in my childhood memory, even as the soundtrack from the record filled my head. That’s when I began collecting postcards of sepia-toned portraits of Native American chiefs.

On another trip to North Dakota to take photographs, I crawled to the edge of a cliff where Bald Eagles were known to nest, led by a Hidatsa Indian on the Ft. Berthold Reservation, an invited guest to a sacred place known only to the tribe. As we peered over the last bit of sage and rock, an eagle opened its wings and flew east, a good sign my new friend said. He reached down and grabbed a large wing feather from the nest, gathered a handful of sage, took a small ribbon of red felt from his vest pocket, wrapped the sage to the quill of the feather and handed it to me: “You are meant to have this as a gift from the eagle,” he said. I kept that in my hope chest, as well.

When my childhood sports trophies outgrew my bookshelf—and my maturity—I put them in the trunk. Even as an adult I would put little keepsakes in the chest; vintage postcards from Ravello, Italy and Paris, France, and Madrid, Spain, places Edie and I visited, and leftover foreign coins from our travels. When we experienced the Santa Francisco Loma Prieta earthquake of 1989 that knocked down bridges, crumpled freeways and set the Marina District on fire, I saved the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle in the trunk.

Whatever you decide to store in your trunk is up to you. It might hold memories of when you lived in Bend; all the drawings you made at our house sitting at the kitchen counter, the gold medal you earned in your first season of soccer, schoolwork you’re proud of, and new memories in your new home and our visits with you there. Maybe a postcard from the souvenir shop when you visit the San Diego Zoo for your birthday. Or, it may just be a convenient and safe place to store your hand controllers when you’re not playing Madden Football to keep them safe from your little brother, Jack. If the utility of a physical trunk to hold artifacts of your life is useful to you, use it that way.

As you grow older, the chest may become a representation of your Norwegian heritage and help you feel grounded. I think you’ll also find it has a spiritual component, a lid that rises up and opens a world to a long line of ancestors, your people that have come before and are part of your DNA, including me. One day you may pass the chest on to your own grandson for him to store his keepsakes in and to know his family story.

To learn more about Rosemaling view this 12 page booklet online: https://issuu.com/vesterheim/docs/vesterheim-rosemaling-booklet?e=32536419/61151140*

Lars! What a treasure! Not just the chest , but the background and history to go with it. Writing it down preserves it for a time when Lars the Younger can appreciate it and cherish it. Maybe pass it on to his son one day, maybe even one named Lars. It’s a great way to pass on stories to the next generation. Love the pictures that take me back to another place and time, the history comes alive again with your writing and a special heirloom. Lucky boy!!